Tasmanian Edward Francis McGinty (known as ‘Barney’) was 23 years old when the first World War broke out. He signed up the following year, and from then on spent the entirety of the war in the Middle East using his experience as a jockey with the Tasmanian C Squadron of the 3rd Light Horse Regiment. Like many servicemen, his wartime service was a combination of active service, behind-the-scenes activities of war, illness in hospital, plus a few occasions of less than exemplary conduct. There is also evidence that he harboured the effects of the war for the rest of his life until he died in 1935.

The youngest of 12 children, Barney grew up in the Burnie region of Tasmania, where he worked as a jockey. In July 1915, a recruiting event was held at the Burnie Theatre, where many stirring addresses encouraged young men to volunteer. At the conclusion, 25 young men (including 24-year-old Barney) mounted the stage to cheers and prolonged applause. After this, Barney spent several months training, first at the Claremont Camp in Tasmania, and then at the Broadmeadows Camp on the outskirts of Melbourne.

Barney was assigned to the 12th reinforcements of the 3rd Light Horse Regiment (LHR) and with 42 other Tasmanian men, embarked the HMAT Ceramic which departed Melbourne in November 1915 bound for the Middle East. Australia’s presence in the Middle East for the entirety of WW1 was due to the fear that the Turks, who were allies with Germany, would take control of the Suez Canal, which would have disastrous consequences on the Allies ability to supply the fronts in Europe.

Before Barney joined them, the 3rd Light Horse Regiment’s first role in the war was as part of the Gallipoli offensive. The men were probably relieved (quite possibly battle-weary or cynical) when they were sent to Egypt early in 1916. Along with the rest of the 12th reinforcements, Barney joined the 3rd LHR at the start of March in 1916 when the regiment was in western Egypt. Shortly after Barney joined the regiment, they travelled by overnight train to Girga in upper Egypt. C Squadron spent some time in Girga; they were in reserve, manning night outposts, guarding the station, and policing the town. Barney spent the remainder of the war with C Squadron of the 3rd Regiment, serving through Egypt, Sinai and Palestine.

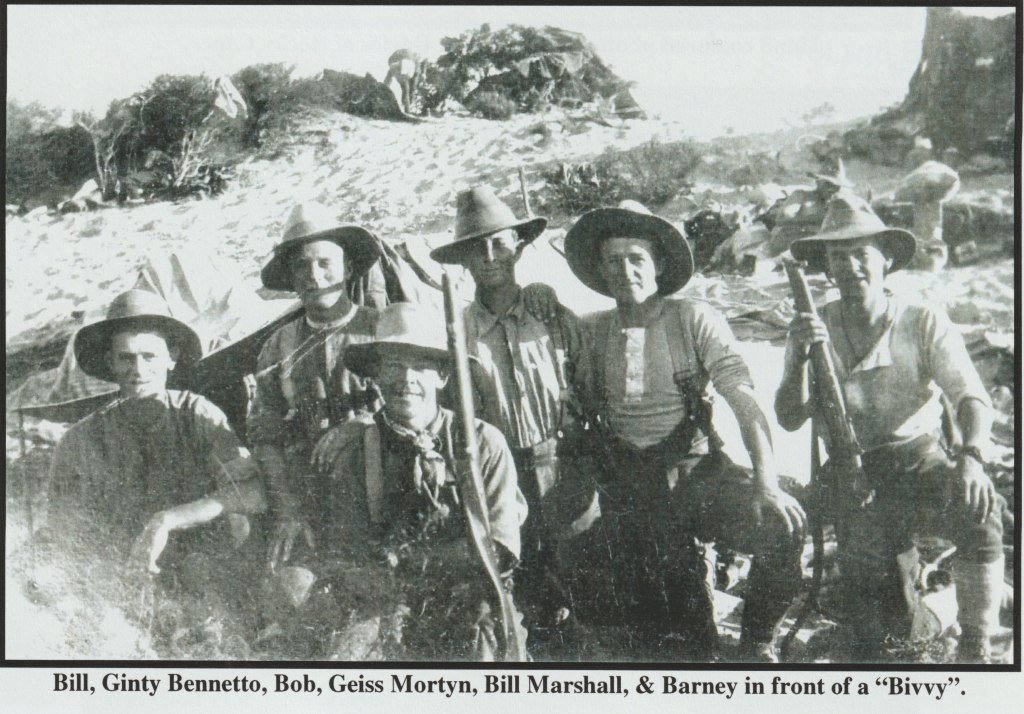

Barney would have been part of a 4 man section who worked together in all aspects of life. In battle the four men would approach the action and dismount; three would fight as infantry, leaving one of the four behind to care for the horses. Ten of these four-man sections made up C squadron, which was made up predominantly of Tasmanian men. Together with A and B squadrons (from South Australia), C Squadron was part of the 3rd Light Horse Regiment. This 3rd regiment, along with the 1st and 2nd regiments, made up the 1st Light Horse Brigade.

The 3rd LHR were involved in battles that took place at Gaza, Romani, Es Salt and Magdhaba. The battle of Romani was infamous because the horses went without water for 59 hours straight, and each man had only one water bottle during that same time period. The 3rd Regiment also had a supporting role in the famous battle of Beersheba on 31 October 1917. On that day, Barney’s regiment was part of a minor offensive to take Tel-El-Saba, a small town 5km east of Beersheba. The Turks had thought that “no one would be mad enough” to attempt an attack from the east due to the lack of water and difficult terrain. Even so, the Australians attacked, and were “swept by machine gun and rifle fire and many casualties were sustained”, the 3rd regiment losing 11 men and having 18 wounded. Despite the Turk’s over-confidence, el-El-Saba did fall, and elsewhere the town of Beersheba was in allied hands by the end of the day.

https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C952527

When the squadron was not involved in active combat, there were many other activities they were involved in; moving from one site to another, waiting for orders, manning observation posts, making camp, constructing and maintaining roads and bridges, maintaining stores and supplies and watering and resting the horses. Private Kemp, a fellow soldier of Barney’s who had also arrived on the Ceramic, noted in a letter to home that “[they] apparently have nothing else to do with a lot of us, as we are constantly packing up and shipping from one camp to another. We just get nicely settled down in one camp when suddenly the order comes to pack up, and away we go to some new place”. Sometimes the men would be able to take a few days leave in a location such as Jerusalem or Bethlehem, or even travel from where ever they were stationed, to Egypt.

The supply of water was key in successful operations in the Middle East. In addition to the water the men required in the hot dusty conditions, the horses required more than 20 litres a day. During the hot and dusty weather, the men would sometimes deal with the heat by going with the horses into the Nile River; unfortunately this meant that many of them contracted the blood parasite bilharziasis from the contaminated water.

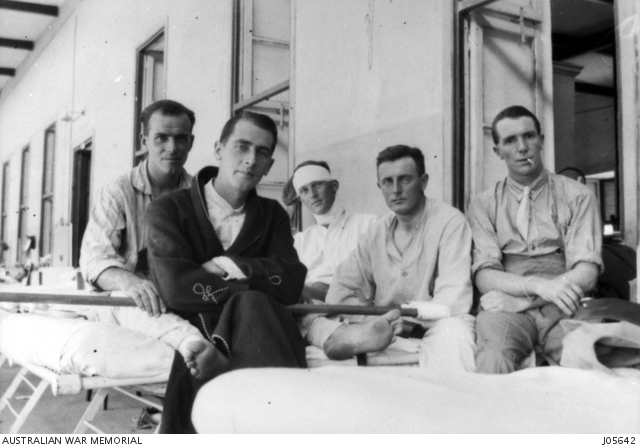

Barney’s service record shows that he suffered from ill health a number of times during the war. Only a month after joining the 3rd LHR (in March 2016) he spent about a week away from active service for a bout of tonsillitis, when he was hospitalised in the No 3 Auxiliary Hospital in Heliopolis. He suffered from an undiagnosed fever in June and July of that year also, this time being admitted to the 31st General Hospital. In October 1917, he suffered a kick to the back from a horse. It must have been quite a serious injury, given the detailed report in his service record, and the fact that he was certified by Lt Col Bell as being in no way to blame for the incident. August 1918 saw him in hospital again with an undiagnosed fever.

https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C3697

Barney’s military record suggests that he wasn’t the perfect soldier. In June 1918, he was disciplined for being in Jerusalem without a pass, “telling a falsehood” and having alcohol in his possession; he was penalised 7 days pay. In May 1919, he was disciplined for going absent without leave (AWL) and giving a false name; punishment was forfeit of 4 days pay. A month later, he went AWL again from Port Said Rest Camp and forfeited more pay. These last two incidents occurred after the surrender in the Middle East, so it’s easy to imagine that the importance of ‘keeping the rules’ was not high for a serviceman who had been at war for 4 years.

There is every chance that Barney was also involved in a more serious misdemeanour. In December 1918, a New Zealand trooper was murdered by a thieving Bedouin civilian in Palestine. Many Australian and New Zealand servicemen were tired of being looted often by the Bedouins and felt the action from their superiors was unsatisfactory. They decided to take matters into their own hands and, without command or sanction, attacked the nearby village of Surafend where the murderer was believed to be hiding. Many civilians were killed, possibly women and children also. Ted O’Brien, a C Squadron member, was interviewed in his later years and stated he believed that most of C Squadron was actively involved in the killings.

The war was over in the Middle East when Turkey surrendered on 30 October 1918, but it would be considerable time before Barney made it back to Australia. In March 1919, still in Egypt, he was admitted to hospital with jaundice and spent most of the remainder of his service time in medical care. His records state that he was transferred to Port Said Rest Camp in April 1919, and left for Australia on the ship ‘Dunluce’ another 3 months after that. The ‘Dunluce’ was a hospital ship; Barney was ‘discharged’ from hospital part way through the voyage home; presumably, he was recovering (from what illness is unknown) as the voyage progressed. The 6-week voyage ended at Melbourne, and a few days later Barney travelled to Hobart. Eight months passed after the end of the war before he was discharged from the AIF at Hobart, on 10 April 1920.

Barney’s rank during the war is unclear (he is referred to as either Trooper or Private) but there is little evidence that he achieved any significant promotion of rank whilst on active service.

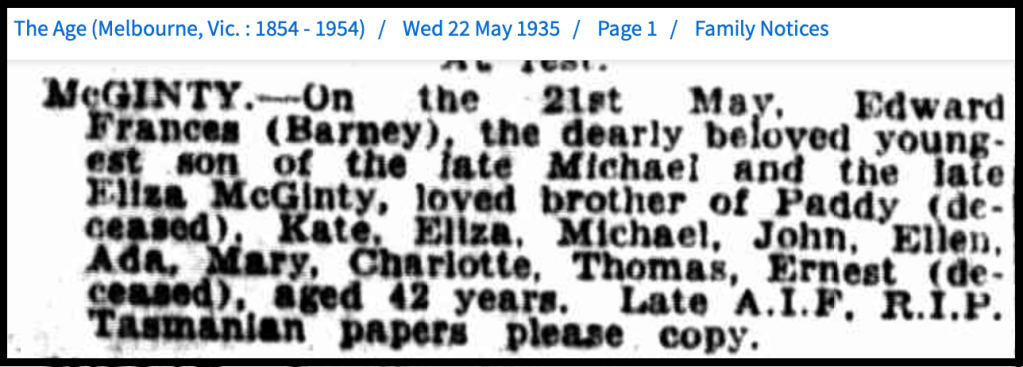

The story of Barney’s war experience does not end with his return to Australia. Little is known of his life immediately after the war, but he eventually died in 1935 in Gresswell Sanitarium of pulmonary tuberculosis (TB). The sanitarium, in Bundoora, Victoria was established to treat TB patients, many of whom were WWI soldiers who had succumbed to the disease “where close living quarters, particularly in tuberculosis-infected countries in the Middle East [had] increased the risk of infection”; it must be assumed that Barney had been living with TB since he had returned from the Middle East and had finally succumbed to it. Although it is known he was loved by his brothers and sisters (his parents were both dead, and there is no record of wife or children), today his grave in Fawkner Cemetery is unmarked.

It could be said that Barney’s service for Australia in the Middle East during World War One was nothing remarkable; he was not awarded any special medals of valour, was not known to achieve any promotion, nor is he now well-known because of his service. But nonetheless he deserves to be remembered just as the most highly decorated soldier does. The “war to end all wars” was fought not just by the famous and decorated, but also by the effort of many ordinary soldiers just like Barney McGinty.

Sources

Australian War Memorial, ‘3rd Australian Light Horse Regiment’, https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/U51037, accessed 17 July 2021.

Bradley, Phillip, Australian Light Horse: the campaign in the Middle East, 1916-1918, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2016.

Cameron, David W, The charge: the Australian Light Horse victory at Beersheba, Viking, Australia, 2017.

Daley, Paul, Beersheba: a journey through Australia’s forgotten war, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2009.

Death certificate of Edward Francis McGinty, died 21 May 1935, Victorian Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages, 14320/1935.

‘Deaths’, The Age, 22 May 1935, p. 1.

Jack, Margaret, ‘Gresswell and tuberculosis’, Mont Park to Springthorpe: Springthorpe Heritage project, n.d., https://www.montparktospringthorpe.com/gresswell-and-tuberculosis, accessed 29 June 2021.

‘News from Egypt’, Port Fairy Gazette, 6 April 1916, p 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article88006821.

Pickering, Peter James, Tasmania’s A.I.F. Lighthorsemen C squadron 3rd Light Horse Regiment, Peter James Pickering, Ridgeway, 2006.

Service record of Edward McGinty, First Australian Imperial Force Personal Dossiers, 1914-1920, National Archives of Australia, B2455.

‘The call of empire: recruiting campaign at Burnie’, The North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times, 28 July 1915, p. 2, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article64616554.

Unmarked grave of Edward McGinty, Fawkner Memorial Park, Fawkner, Victoria, Roman Catholic Section H, Grave 2126, accessed 18 January 2018.